Isaac Newton once wrote, “If I have seen further, it is by standing on the shoulders of giants.” (That’s sometimes been interpreted as a sarcastic remark directed at his rival Robert Hooke, who may have had a pronounced curvature of the spine, although many historians dispute this.) But Newton was expressing the truth that all science proceeds from previous achievements — and even the most famous scientists relied on the diligent and sometimes thankless work of their little-known colleagues. In celebration of these unsung stalwarts of science, here are 32 important scientists you’ve (probably) never heard of.

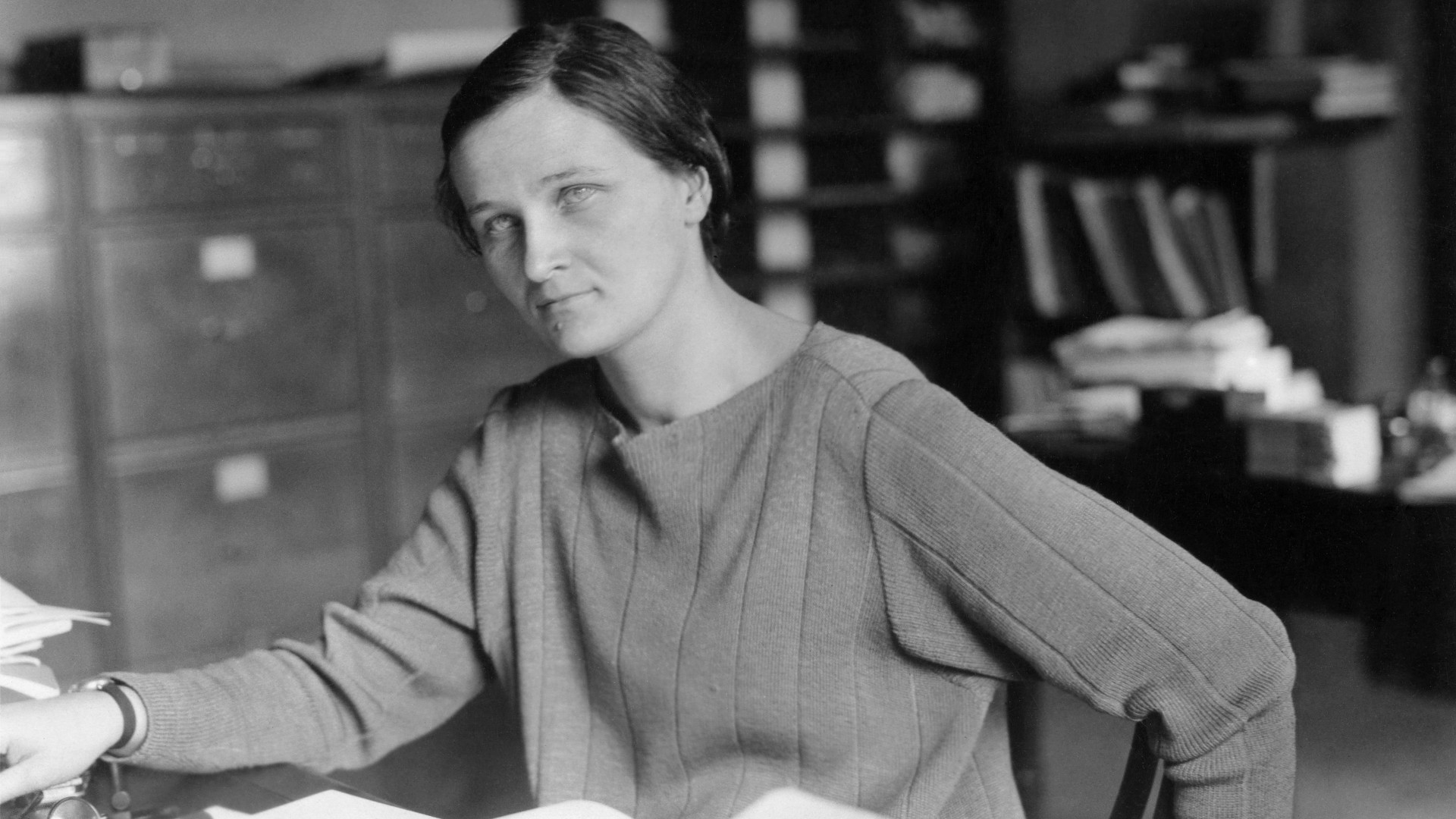

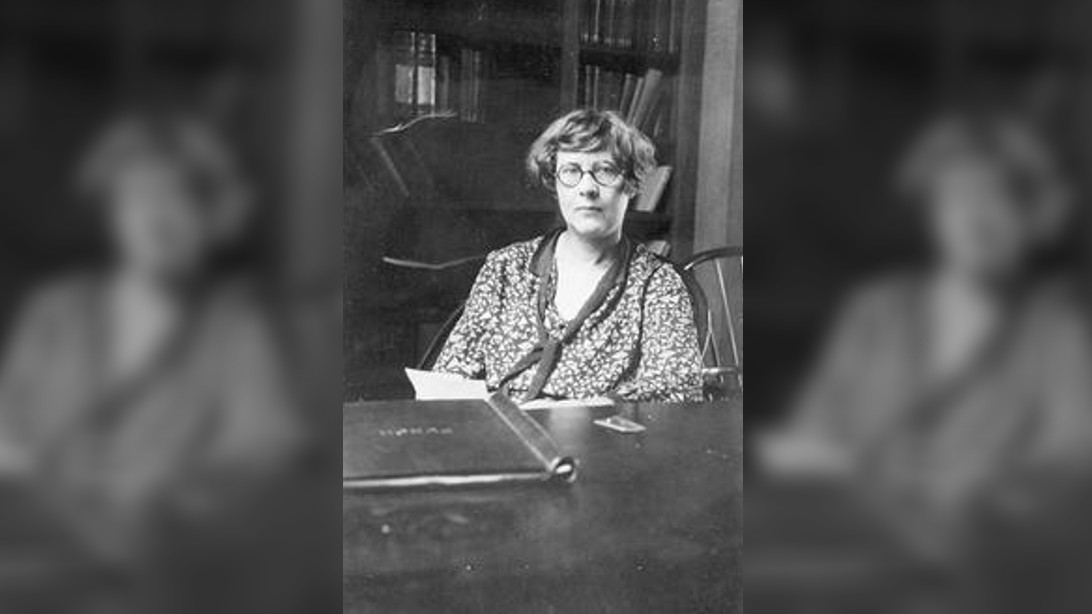

Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin

In her 1925 doctoral thesis, the astronomer Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin proposed that stars are composed primarily of hydrogen and helium — an idea that revolutionized science but was initially met with skepticism. According to the American Museum of Natural History in New York City, Payne-Gaposchkin was renowned for her work on variable stars, and wrote several books. She was born in England in 1900, immigrated to the United States to study astronomy at Harvard College Observatory, and died in 1979.

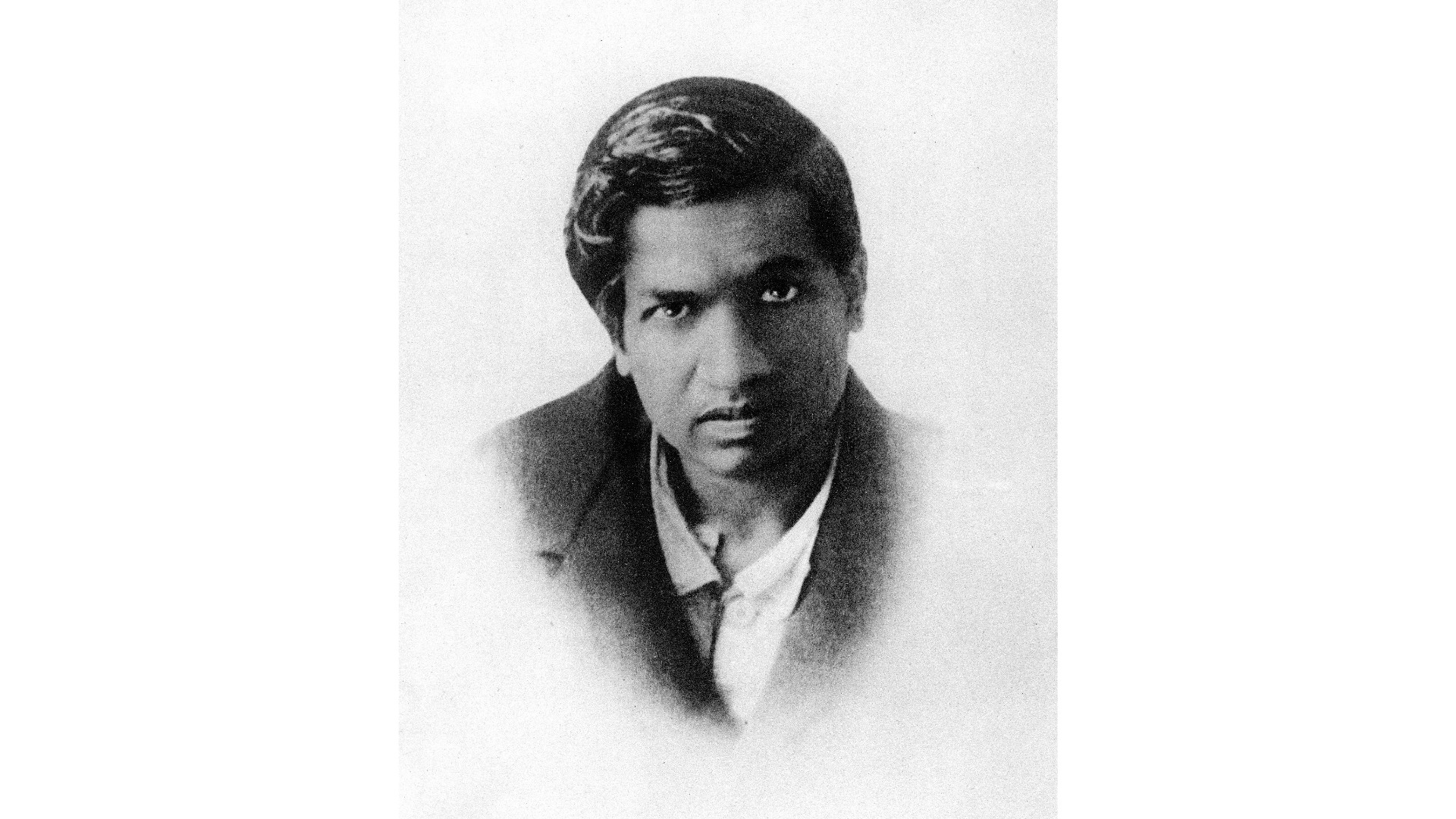

Srinivasa Ramanujan

Born in Tamil Nadu, India, in 1887, mathematician Srinivasa Ramanujan caught the attention of British mathematician G. H. Hardy, with whom he collaborated and who sponsored his move to Cambridge in England. According to Encyclopedia Britannica, Ramanujan is best known for his work on number theory, infinite series and fractions, while several areas of his work — including elliptical functions and Riemann zeta functions — still inspire modern mathematical research. Ramanujan died in 1920 at the age of 32; his cause of death is debated.

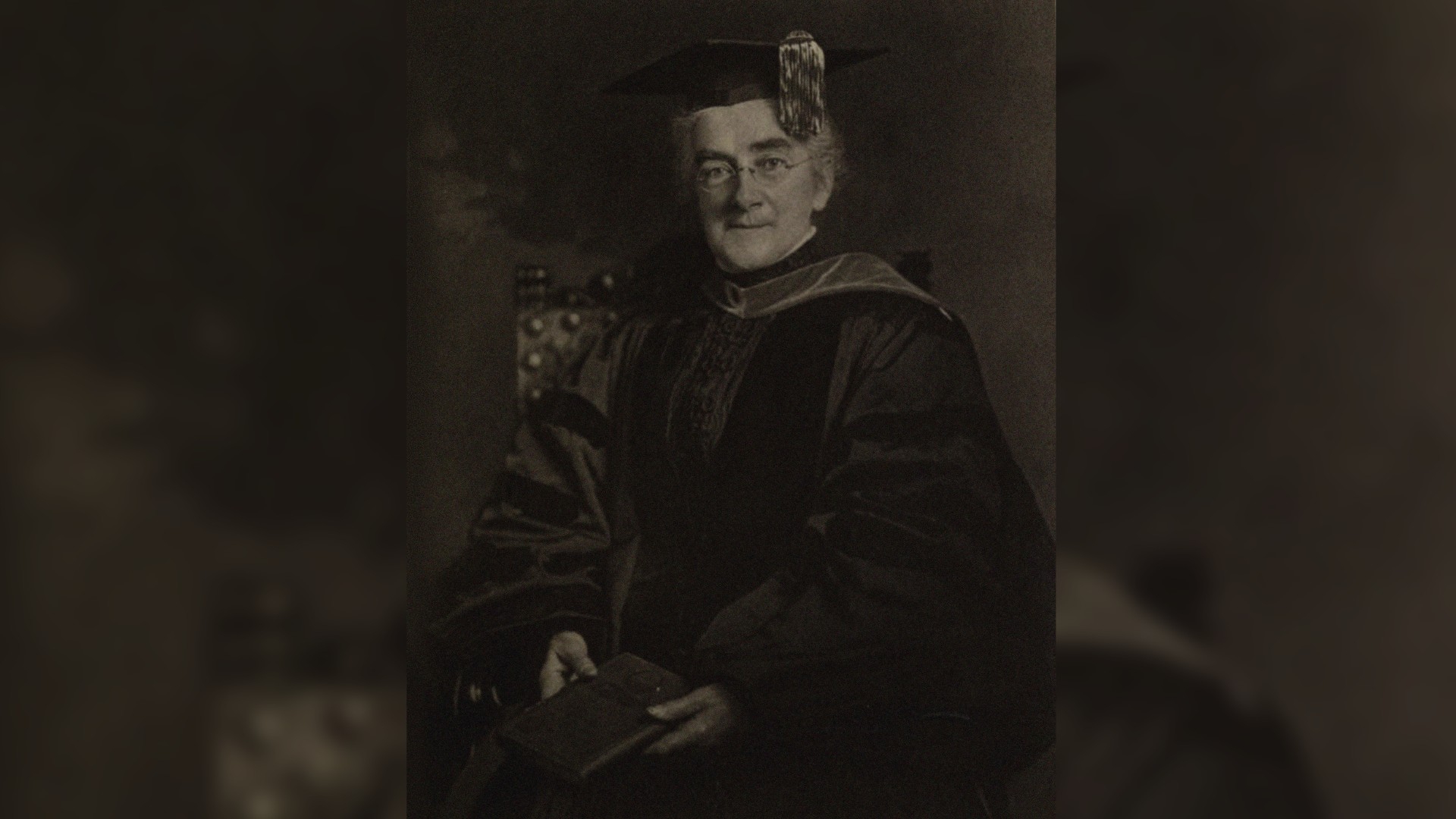

Ellen Swallow Richards

In 1868, the pioneering American engineer and chemist Ellen Swallow Richards (1842-1911) became the first woman admitted to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where she earned a degree in chemistry. According to Cornell University, she is regarded as the founder of the field of home economics, which applied scientific principles to domestic life, and she is considered one of the first environmental engineers thanks to her groundbreaking research on water quality and sanitation.

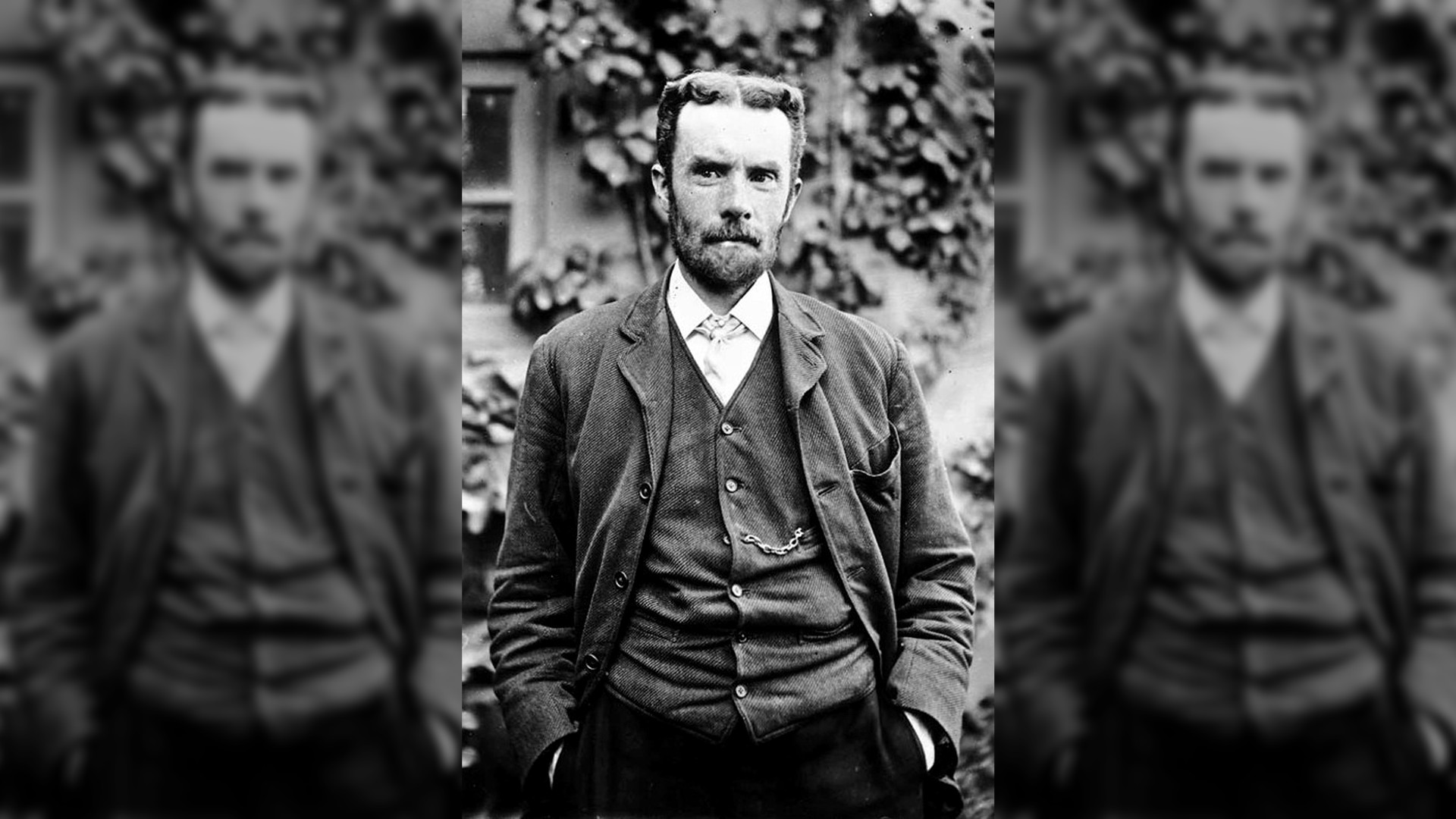

Oliver Heaviside

Born in London in 1850, mathematician and physicist Oliver Heaviside made developments in electromagnetic theory. These include work on transmission lines that advanced long-distance telephony and his prediction of a layer of Earth’s ionosphere — sometimes called the Heaviside layer, or the Kennelly-Heaviside layer — that reflected some radio waves and allowed radio broadcasts around Earth’s curvature. Heaviside died after falling from a ladder in 1925.

Dorothy Hodgkin

British chemist Dorothy Hodgkin is renowned for her pioneering work in X-ray crystallography and her development of methods for determining molecular structures using X-ray diffraction. Among other compounds, she researched the structures of drugs such as penicillin and insulin, which had significant implications for medicine and biochemistry. Hodgkin was born in Cairo, Egypt, in 1910; won the Nobel Prize in chemistry in 1964; and died in the U.K. in 1994.

Matilda Moldenhauer Brooks

Born in 1890, Matilda Moldenhauer Brooks was an American cellular biologist who made important contributions to toxicology. They include her 1932 discovery that the dye methylene blue, which is commonly used to stain organic samples in biology, can also act as an antidote to poisoning by carbon monoxide and cyanide. She was also an advocate for the role of women in science and faced challenges in securing a research position at the University of California because her husband, Sumner Cushing Brooks, was also a researcher there and anti-nepotism policies prevented her appointment. She died in 1981.

Nettie Stevens

The American geneticist Nettie Stevens was one of the first scientists to identify sex chromosomes. Her studies of mealworms showed that males produced two distinctive types of sperm, which always resulted in either male or female offspring; and her meticulous research showed the presence of X or Y sex chromosomes in the sperm. Her work laid the foundation for the modern understanding of the X-Y sex determination system, which is now a cornerstone of genetics. Stevens was born in Cavendish, Vermont in 1861 and died in Baltimore in 1912.

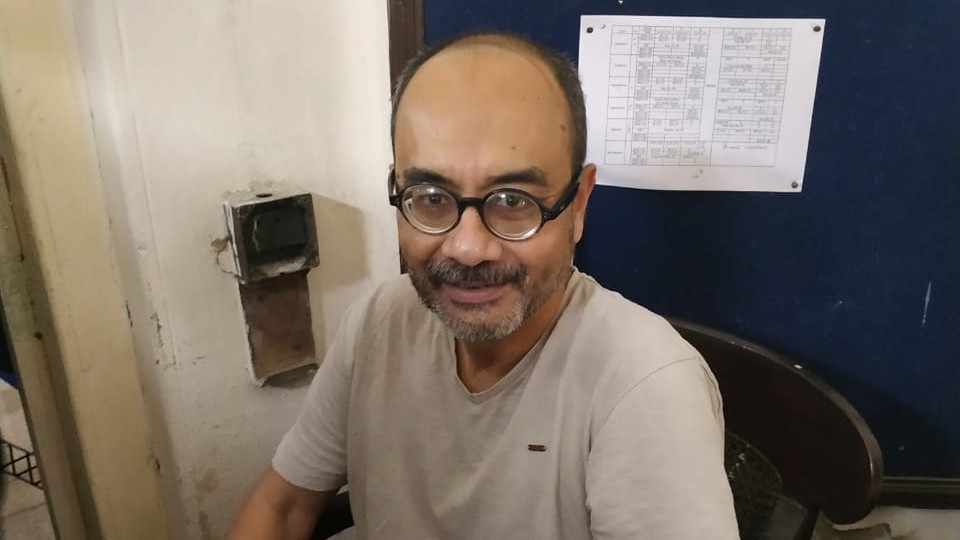

Ashoke Sen

Indian theoretical physicist Ashoke Sen is a pioneer of string theory and noted for his contributions to quantum field theory and black hole entropy. Sen was born in Kolkata in 1956 and has studied in the United States and the United Kingdom; his research has laid the foundations for explorations into the fundamental nature of the universe. He now lives and teaches in Bangalore, where he is a leading voice in the pursuit of a unified theory of everything.

Hermann Minkowski

Mathematician Hermann Minkowski is most famous for developing a geometric interpretation of Einstein’s theory of special relativity. Among his other innovations, he proposed the idea of space-time, which combines the three physical dimensions of space with the fourth dimension of time into a unified mathematical framework. He also made important contributions to number theory and the geometry of numbers. Minkowski was born in Lithuania in 1864, when it was still part of the Russian Empire, and died in Germany in 1909 at the age of 44.

Prahalad Chunnilal Vaidya

Indian physicist and mathematician Prahalad Chunnilal Vaidya (1918-2010) made important contributions to general relativity, including a solution to Einstein’s field equations that describes the gravitational field of a radiating star; earlier solutions had assumed only a nonradiating mass. He also contributed to the professional advancement of science in India after its independence from Britain in 1947, which included forming the Indian Association for General Relativity and Gravitation and leading the Indian Mathematical Society.

Maurice Hilleman

American microbiologist Maurice Hilleman (1919-2005) was a pioneer of vaccinology and is thought to have saved millions of lives. In the 1950s, while working for the U.S. Army, he identified the mechanisms by which influenza viruses mutate, which allowed the creation of better vaccines and prevented the possible outbreak of flu pandemics. He also developed vaccines for hepatitis B and meningitis, and his vaccines for measles, mumps and rubella were combined into a single injection, known as the MMR vaccine, to simplify childhood immunizations.

Emmy Noether

German mathematician Amalie “Emmy” Noether (1882-1935) made important contributions to abstract algebra, particularly in what are known as ring, field and group theories, which laid the foundations for modern algebra. Her “Noether’s theorem” linked symmetries in physical systems with the principles of energy conservation and is now a cornerstone of physics. Noether was born in Germany but emigrated to the United States in 1933, after her university professorship, along with those of other Jews, was revoked by the Nazis.

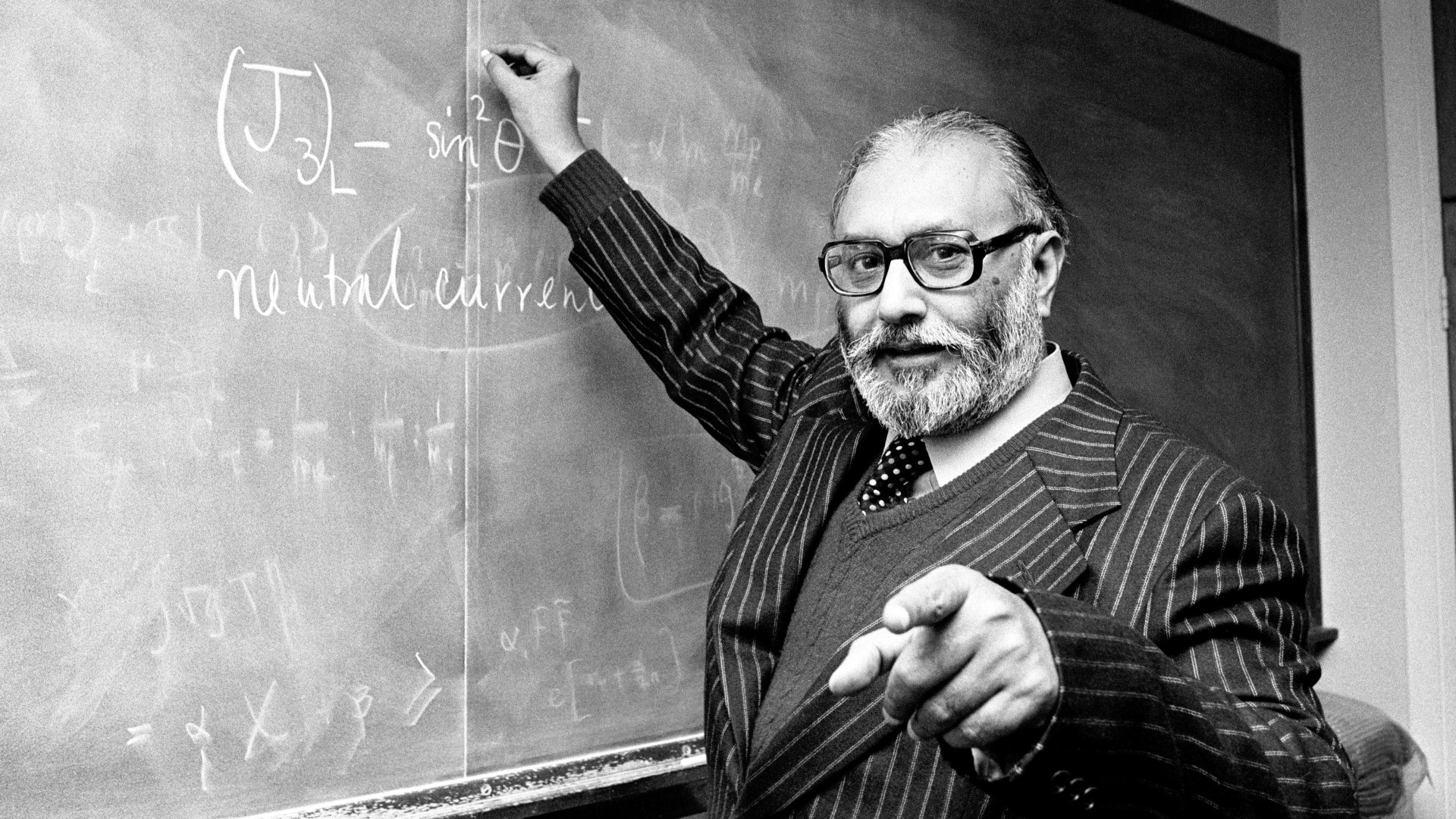

Abdus Salam

Abdus Salam (1926-1996) was a Pakistani theoretical physicist who contributed to the scientific understanding of fundamental forces. One of his key achievements was the theory of the electroweak force, which combined the electromagnetic force and the weak nuclear force — a step toward a unified theory of everything. With his colleagues, Salam was awarded the 1979 Nobel Prize in physics for this work. Salam also championed scientific collaboration between countries and co-founded the International Centre for Theoretical Physics in Trieste, Italy, in 1964.

Saharon Shelah

Mathematician Saharon Shelah is a leading figure in model theory, which explores the relationships between logical structures and their interpretations, and set theory, which studies sets of mathematical objects and their properties. Shelah’s work examines the foundations of mathematics — particularly the structure and properties of mathematical objects. He was born in Jerusalem in 1945; in 2001, he won the Wolf Prize, one of the most prestigious awards in mathematics.

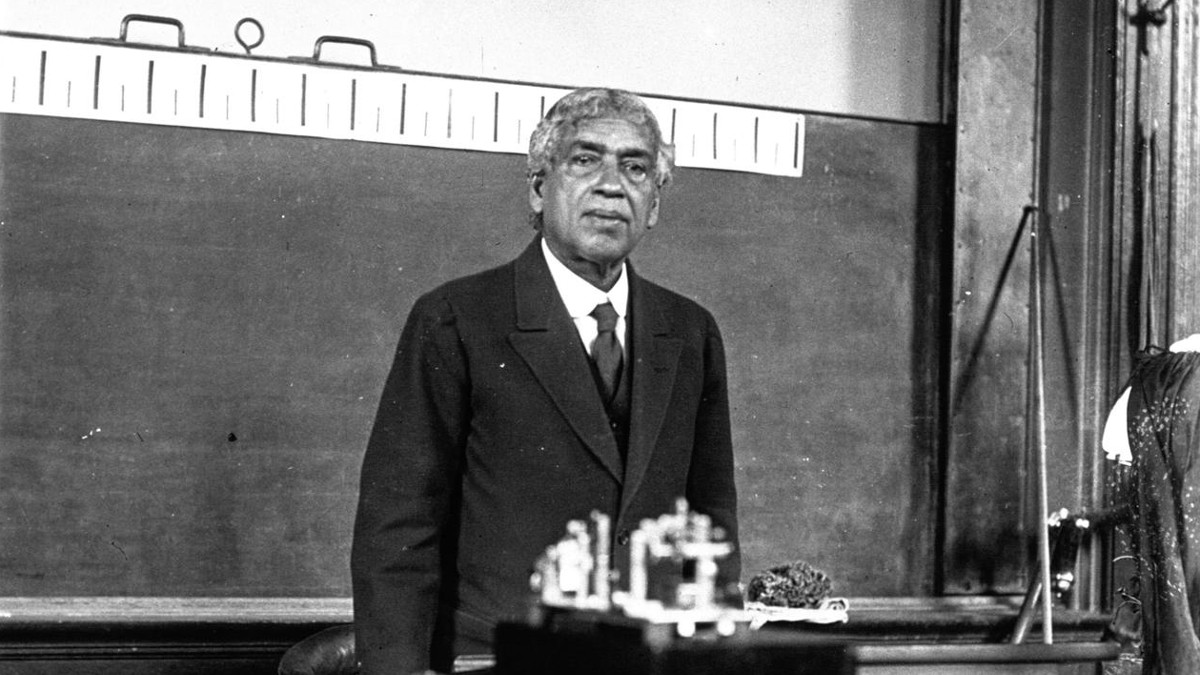

Jagadish Chandra Bose

Indian polymath Jagadish Chandra Bose (1858-1937) is known for his contributions to the fields of physics, botany and biology. He invented an instrument called the crescograph, which can detect minute changes in plant tissues in response to fluctuations in light, temperature and other factors. His experiments in this field challenged the prevailing view of plants as passive entities and showed they were sensitive to their environments. He also conducted research into radio waves and independently achieved wireless transmission in 1895.

Aristarchus of Samos

Aristarchus of Samos was an ancient Greek mathematician and astronomer who lived from roughly 310 to 230 B.C. in the city-state of Samos. He is thought to be the first to develop the heliocentric model of the solar system, in which the planets orbit the sun. A few centuries after Aristarchus, however, most astronomers preferred the geocentric model, in which the sun and planets orbited the Earth; and that was the dominant theory until it was challenged in the 16th century A.D. by the Polish mathematician and astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus. Copernicus had developed his own heliocentric model, and seems not to have known about Aristarchus.

John Michell

No portrait survives of the early English scientist John Michell (1724-1793) but he made important contributions to several scientific fields, including astronomy and geology. Michell was a friend of the astronomer William Herschel and was the first to determine that double or “binary” stars were in fact orbiting each other. Before this, Herschel and other astronomers believed the many double stars they had seen were just tricks of alignment, and that one of the stars was much further behind the other. But Mitchel showed there were far too many observations of double stars than could occur at random. He also showed that star clusters like the Pleiades could not have occurred at random, which indicated the stars in such clusters shared a common origin. Michell was the first scientist to apply statistics to astronomy; statistical techniques are now a cornerstone of the field.

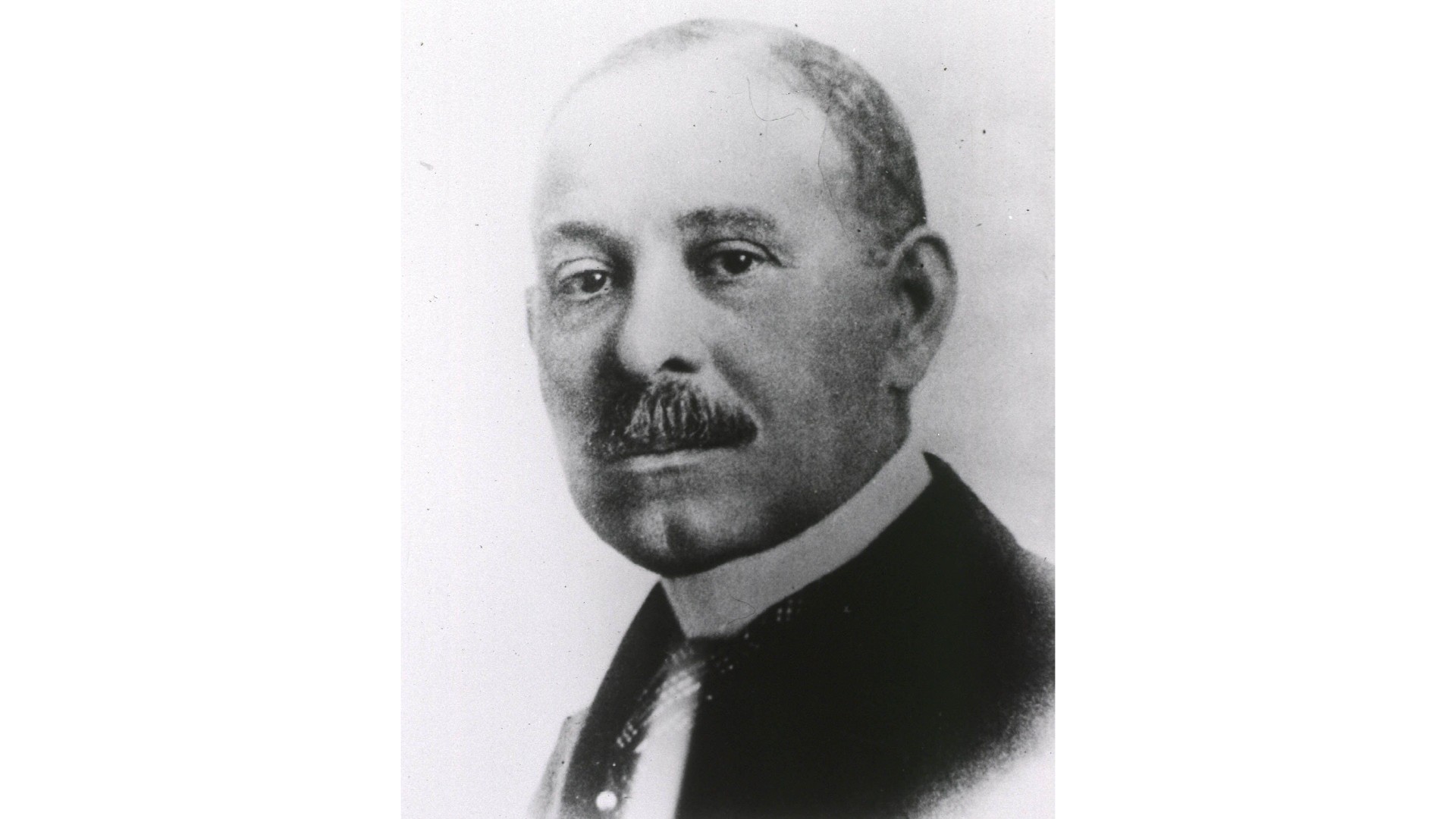

Daniel Hale Williams

Daniel Hale Williams (1858-1931) was a pioneer in modern medicine and an important Black American scientist. He performed the world’s first successful heart surgery in 1893, by controlling the bleeding of a man who had been stabbed in a fight. Williams co-founded Provident Hospital in Chicago, which was the first Black-owned and -operated medical institution in the United States. He was a vocal critic of racial disparities in health care and co-founded the National Medical Association, a professional organization for Black doctors facing limitations in the medical community.

Mikhail Dolivo-Dobrovolsky

Mikhail Dolivo-Dobrovolsky was born in 1862 in Russia. He was an important electrical engineer and invented the first practical alternating-current (AC) induction motor that could easily convert electricity into mechanical power. Earlier AC motors were complex and unreliable, but Dolivo-Dobrovolsky’s invention paved the way for the wide-scale adoption of national AC grids. He also designed transformers to vary AC voltage, which allowed it to be transmitted over long distances. In the 1890s, he helped build the world’s first long-distance AC power transmission system between Frankfurt and Offenbach, Germany. He died in 1919.

Marguerite Perey

French nuclear chemist Marguerite Perey, born in 1909, was a student of the Polish-French physicist and chemist Marie Curie. She worked for many years as Curie’s personal assistant at Curie’s Radium Institute in Paris, where she learned how to isolate and purify radioactive elements. In 1935, while studying the radioactive element actinium, Perey discovered the 87th element of the periodic table, which she called “francium” after her home country. She’d hoped the radioactivity of francium would help diagnose cancer in patients, but in fact it was carcinogenic; Perey developed bone cancer and died in 1975.

Sofya Kovalevskaya

Sofya Kovalevskaya, born in 1850, was a Russian mathematician who made important contributions to mathematical methods of analysis, partial differential equations and mechanics. She was the first woman to obtain a modern doctorate and the first woman in Northern Europe to be appointed to a full professorship. Her most notable contribution was the development of the “Kovalevskaya top” — equations that describe a virtual spinning top within a gravitational field — thereby solving what was one of the most complex problems in classical mechanics. She lived in Sweden after the 1870s and died in 1891 at the age of 41.

Émilie du Châtelet

Émilie du Châtelet was an 18th-century French natural philosopher and mathematician who is best known for her translation of and commentary on Isaac Newton’s 1687 book “Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica,” often called the “Principia.” Her commentary made several contributions to Newtonian mechanics, including an additional conservation law for the kinetic energy of motion, and she developed new ideas about the relationship between energy and the mass and velocity of an object. Du Châtelet was born in 1706 and died in 1749 from complications during childbirth.

Hero of Alexandria

Hero (or Heron) of Alexandria was an engineer and mathematician who lived in Alexandria, Egypt, when it was ruled by the Romans in the first century A.D. He is credited with the invention of a steam-powered device called the aeolipile, or “Hero’s engine,” which featured a primitive steam turbine. He also developed the technology behind windmills — an important contribution to civilization. In mathematics, he is best remembered for Heron’s formula, which is a way of calculating the area of a triangle using only the lengths of its sides.

Johann Rudolf Glauber

Born in 1604 in Karlstadt, Bavaria (which in 1871 became part of the German Empire), Johann Rudolf Glauber is considered one of the first chemical engineers, and his inventions often had commercial uses. He was the first to describe “chemical gardens,” in which inorganic chemicals immersed in a sodium silicate solution appear to “grow” into complex structures. In 1625, Glauber discovered sodium sulfate, also known as “Glauber’s salt,” which is now a major chemical commodity used to make detergents and paper. He died in about 1670, possibly from poisoning by the chemicals he used in his work.

Ḥasan Ibn al-Haytham

Ḥasan Ibn al-Haytham, also known as Alhazen, was born in Basra, now in southern Iraq, in about A.D. 965. He lived mainly in Cairo, Egypt, until 1040, during the Islamic Golden Age. He is sometimes called “the father of modern optics” and made important discoveries in the field, including a theory of vision that argued, correctly, that it occurred in the brain. (Earlier theories had suggested light rays were emitted from the eyes.) He also studied reflections, refraction, and the nature of images formed from rays of light.

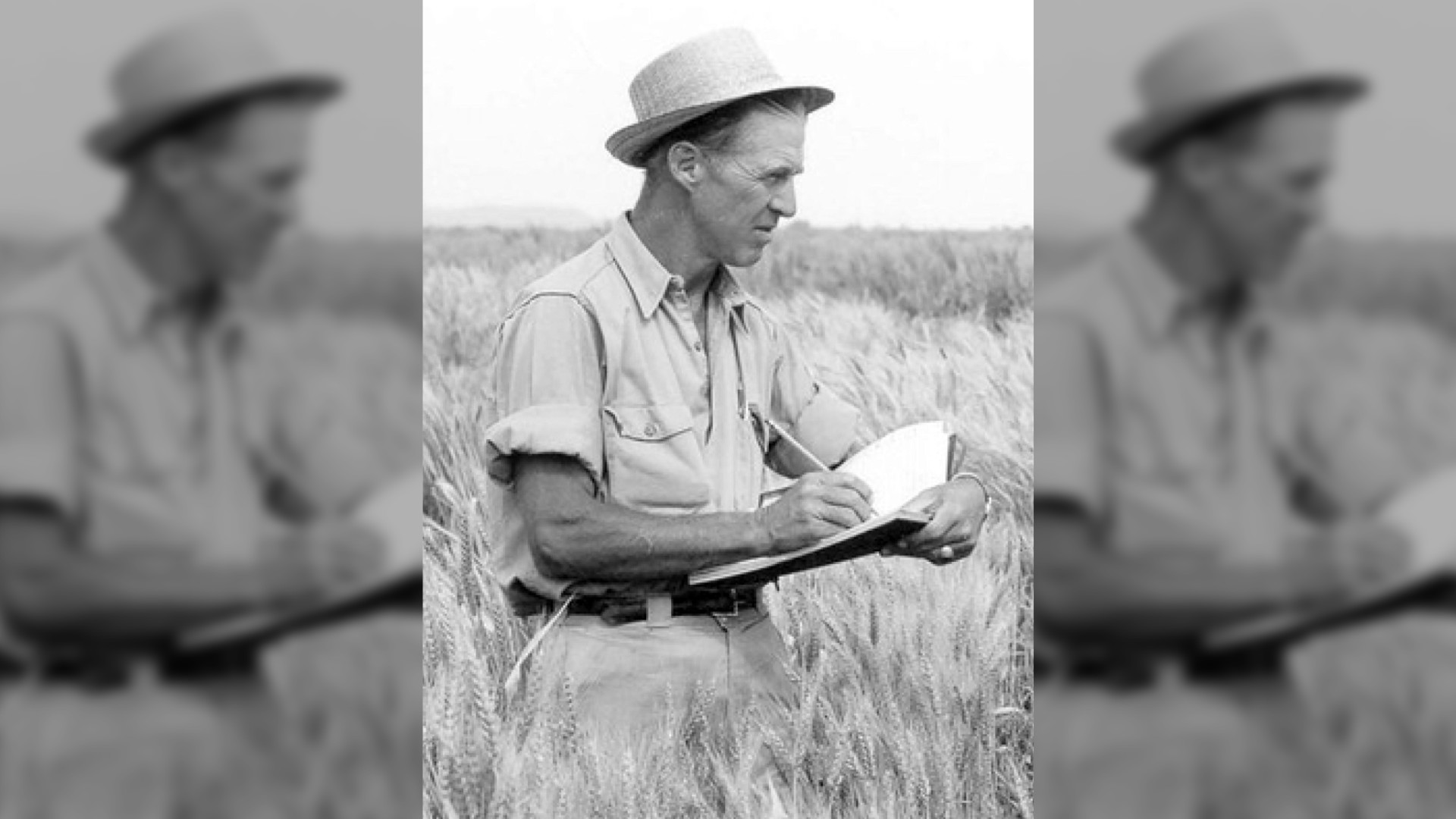

Norman Borlaug

American agricultural scientist Norman Borlaug (1914-2009) is known as “the father of the Green Revolution.” His research contributed to global food production, and he spent decades developing disease-resistant strains of wheat that are now planted around the world. Borlaug also championed the transfer of farming technologies to developing nations, for which he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1970, and stressed the importance of population control to achieve long-term food security.

Annie Jump Cannon

Annie Jump Cannon (1863-1941) was a pioneering American astronomer nicknamed “the census taker of the sky” for her meticulous work classifying stars. She studied physics and astronomy at Wellesley College in Massachusetts and worked at Harvard College Observatory from the late 1890s, where she developed a classification method based on the spectra of stars that was first used by astronomer Edward Pickering. Cannon had exceptional eyesight and classified over 350,000 stars in her lifetime, sometimes at a rate of more than 5,000 stars a month. Her classification system played a crucial role in the development of the modern stellar classification system, which is based on a star’s temperature and surface conditions.

Fritz Zwicky

Born in 1898 in Bulgaria to a Swiss father and a Czech mother, Fritz Zwicky emigrated to the United States in 1925 and studied astronomy at the California Institute of Technology. Zwicky developed many astronomical concepts, and with astronomer Walter Baade described neutron stars and supernovae — the powerful explosions of massive stars. His greatest contribution to science, however, was suggesting that galaxy-scale concentrations of what’s now called dark matter — he called it “dunkle materie” in German — may be the cause of anomalies in the behavior of galaxies within galactic clusters and the orbital speeds of stars at the edges of galaxies. He died in 1974.

Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar

Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar (1910-1995) was an Indian-American astrophysicist who studied the evolution of stars. His most famous research resulted in his determination of what’s now known as the Chandrasekhar limit, which is the point at which a star that has run out of fuel will collapse into a white dwarf. Each of these incredibly dense stellar remnants can be smaller than Earth but have a mass greater than that of the sun. His research expanded into the study of black holes, which initially were not widely accepted but now are regarded as both an important feature of astronomy and possible clues to the nature of the universe. Chandrasekhar shared the 1983 Nobel Prize in physics for his work on stellar evolution.

Ida Noddack

German chemist Ida Noddack (1896-1978) was the first woman to hold a professional position in Germany’s chemical industry. Her most famous discovery, which she made with her husband Walter Noddack and collaborator Otto Berg, was their isolation in 1925 of the 75th element on the periodic table, a rare metal they named “rhenium” after the river Rhine. The element had been predicted decades earlier, and the discovery confirmed the theoretical structure of the periodic table. Noddack was also one of the first scientists to suggest that the nuclei of some elements bombarded with neutrons could split — a phenomenon now known as nuclear fission.

The 19th century American scientist and inventor Eunice Foote (1819-1888) carried out early research on the greenhouse effect, in which some atmospheric gases trap heat from the sun near Earth’s surface. In 1856, she presented a paper at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science demonstrating the effect of the sun’s rays on different gases and suggested this had taken place in Earth’s atmosphere and affected its climate. But Foote, as a woman in the 19th century, was not permitted to read her own paper at the meeting, so a male professor read it on her behalf.

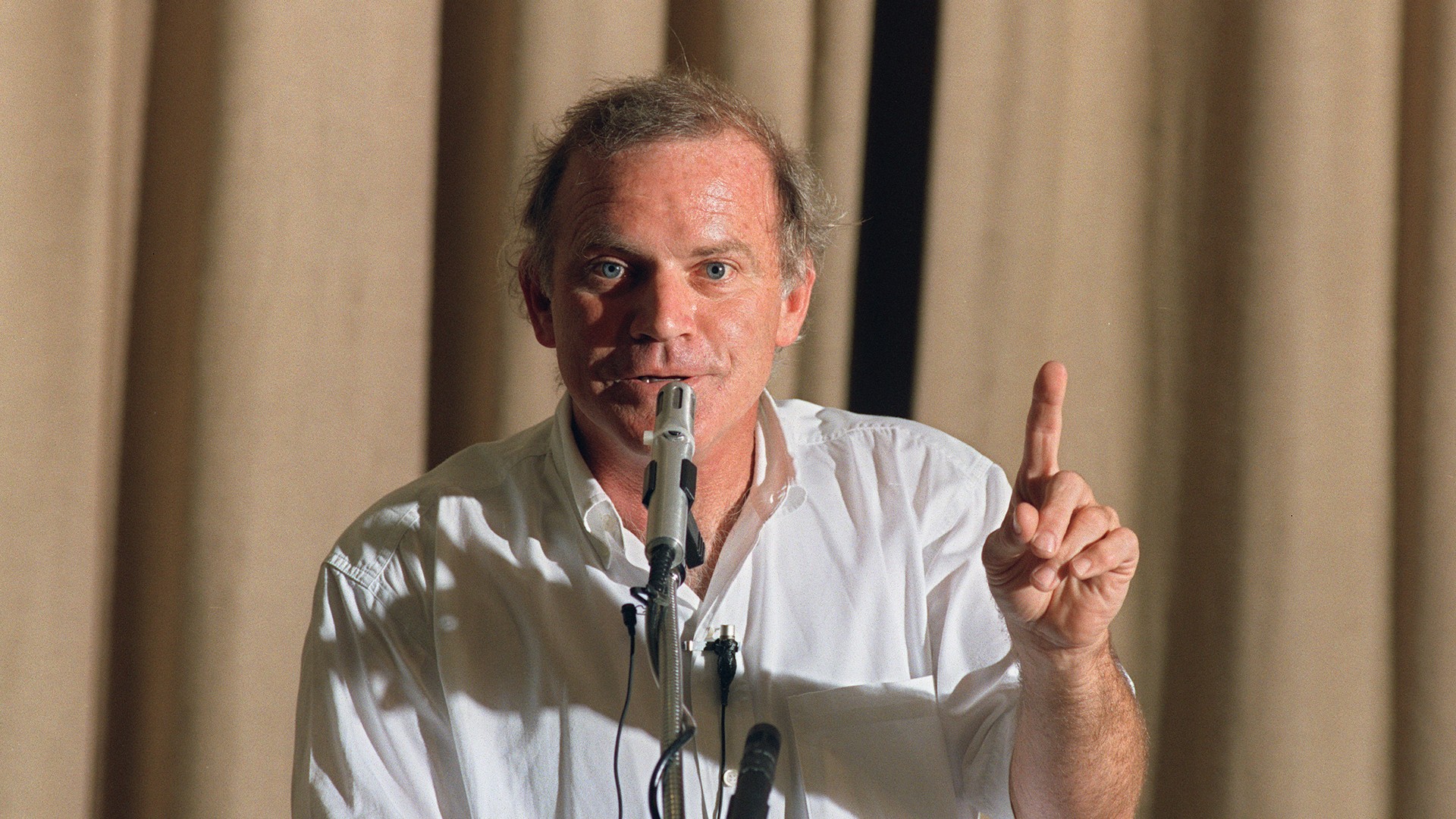

Kary Mullis

American biochemist Kary Mullis revolutionized molecular biology with his invention of the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) technique. He conceived the idea in the 1980s while working for an early biotechnology company. It allows the rapid amplification of specific DNA sequences within a controlled environment, sharply reducing the amount of starting DNA required and cutting the time needed for analysis. PCR can detect DNA from viruses, bacteria and genetic mutations, and it is now a cornerstone of medical diagnostics, genetics, forensics and archaeology. Along with Michael Smith, Mullis was awarded the 1993 Nobel Prize in chemistry for the invention. He was born in 1944 and died in 2019.